Presented at Sarai in February 2019, Startup States was a curatorial investigation into the colonial origins of systems of biometric identification, registration, and control in India and Australia, and their relationship to technics of identification and data-driven governance today.

Modern biometrics began in Bengal in the second half of the 19th century, when the uniqueness of individual fingerprints was discovered and a classificatory system for fingerprints was developed by British Indian civil servants and police. Fingerprinting formed the basis of modern biometrics by creating a metric (i.e. a standardised unit of measurement), and an algorithm (i.e. a systematic mechanism for sorting and retrieving information).

Post-colonial India boasts the world’s largest biometric identification program, known as Aadhaar (meaning ‘foundation’ in a number of different Indian languages). Initially developed to assist in the distribution of welfare and to counter corruption, Aadhaar is now a means of identification for individuals to access a wide range of government and commercial services. After its initiation by the Indian government in 2009, the development of the Unique Identification (UID) program was led by Nandan Nilekani, former CEO of Infosys. Taking direct inspiration from digital platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram that have successfully scaled up to accommodate billions of users, Nilekani adopted the model of a startup, employing a small team of programmers, technicians, and bureaucrats to develop and implement a nation-wide system able to capture and manage the biometric and demographic data of every resident of India. Within 5 years, over 1 billion people had submitted their fingerprints, iris scans, and photographs and received a unique 12-digit Aadhaar number. Today the centralised Aadhaar database holds the biometric profiles of over 1.2 billion people – more than 99% of the population of India.

While the UID program ostensibly benefits millions of people, it also serves to bring individuals formerly unregistered as Indian residents, and hence invisible to the state, out of the shadows of informal economies and online (and in line) into a global neoliberal economy. After a number of data leaks and as the use of Aadhaar expanded far beyond its original remit, public concerns regarding the program’s privacy and surveillance risks were formalised through litigation against the government, resulting in a 2013 Supreme Court interim order that the government could not deny a service to anyone who did not possess an Aadhaar number. Later in 2017, the Supreme Court determined that ‘the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty’ under the Indian constitution – however the court later found that as a voluntary government program, Aadhaar does not breach the right to privacy. Consequentially, Aadhaar continues to be linked to many essential and non-essential services, and remains technicallyvoluntary, though few have the time or patience to navigate Indian bureaucracy without an Aadhaar profile.

A study of this history and these concerns formed the basis of Startup States. The exhibition brought together contemporary artworks and artefacts to consider the governmental provisionality characteristic of colonies and startups; ways in which the economy of surveillance capitalism generates a form of data-driven governance as it codifies, financialises, and regulates daily life; and how the efficiency of such networked governance is being mimicked by nation states through citizen profiling schemes such as Aadhaar.

Exhibited artworks by Abhishek Hazra, Alana Hunt, Ayesha Hameed, Birender Yadav, Ele Carpenter with Raqs Media Collective, Jason Wing, Karthik KG, Moonis Ahmad Shah, and Somnath Bhatt are presented here.

Somnath Bhatt

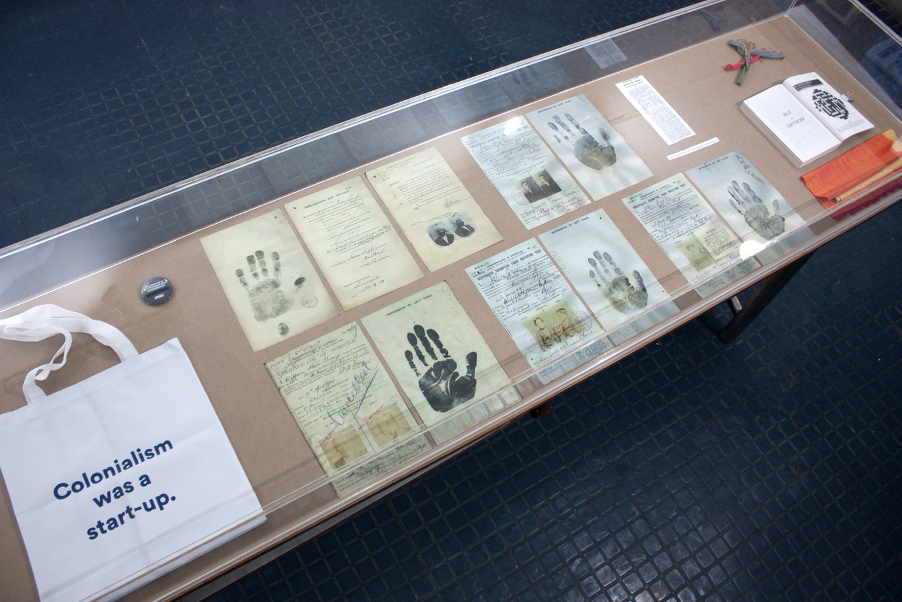

Colonialism Was a Start-up

tote bag (2015)

Mozilla

Aadhaar is Dystopian and Dangerous

badge (2018)

Commonwealth of Australia

Copies of Australian settler profiles, their handprints, and their ‘Certificate Exempting From Dictation Test’, drawn from the National Archives of Australia (1904-1919)

Raqs Media Collective

A Concise Lexicon of / for the Digital Commons

Published in ‘Sarai Reader #03 Shaping Technologies’ (2003)

Ele Carpenter

Embroidered Digital Commons

cotton, thread (2008–), a collective close-reading and close-stitching of the text A Concise Lexicon of / for the Digital Commons.

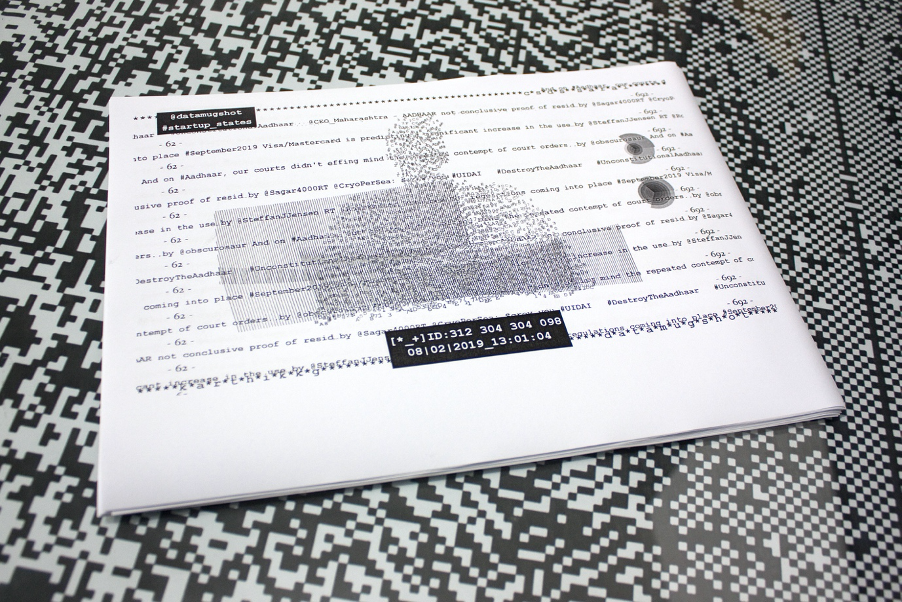

datamugshot

software (processing script for visuals, Pure Data for sound), two desktop monitors, Kinect motion sensor, PC, sound (2017/19)

>> Brute Force >> Merge Sort

HD video loop, 10 mins (2017)

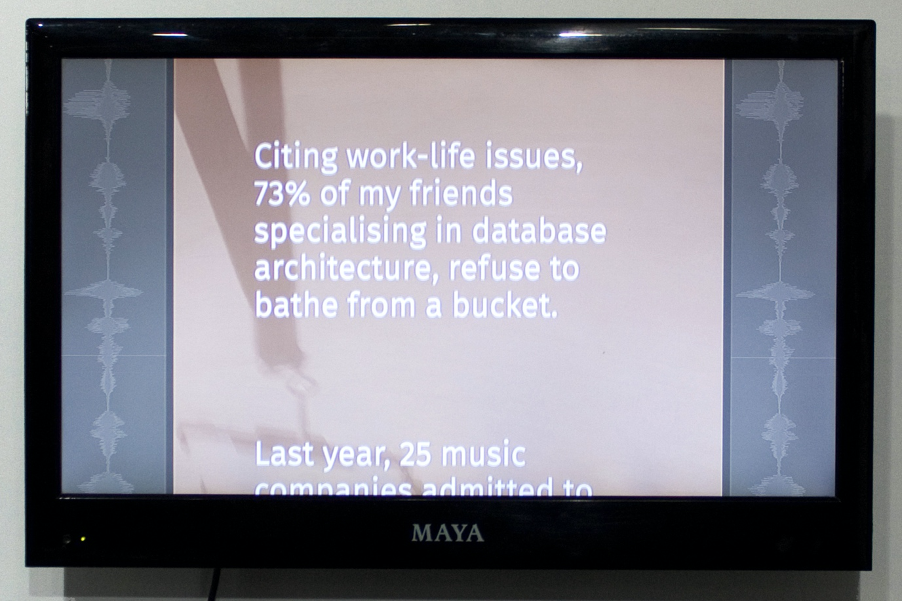

Is My ID Me OR Is It My Dog?

HD video, 10 mins (2010)

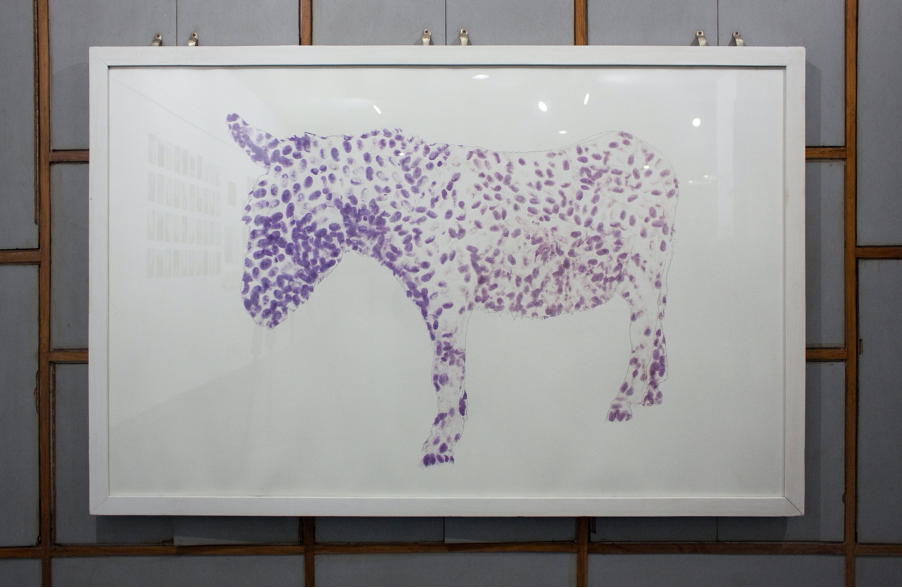

Donkey Worker (Angootha Chap series)

36 x 60 inches, thumb prints on paper (2015)

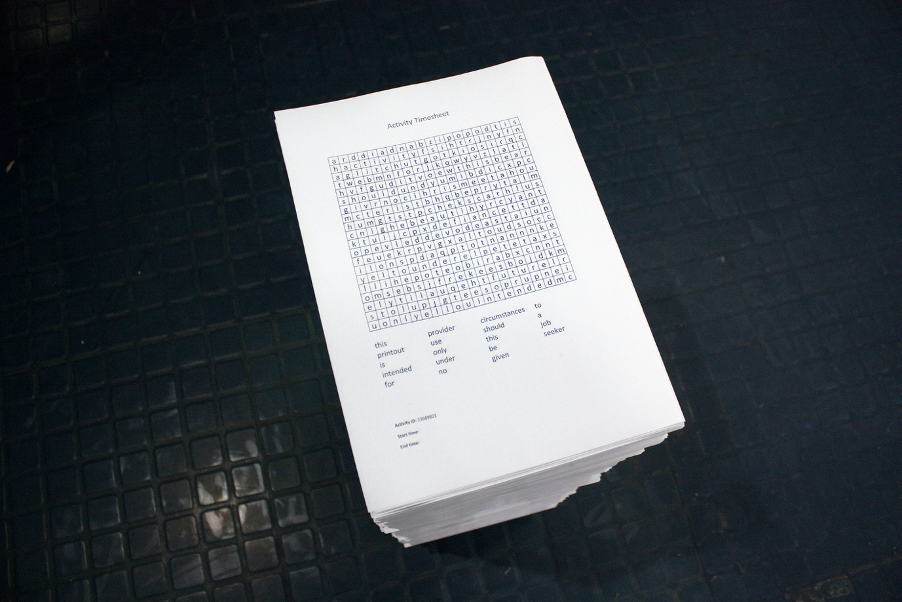

An Activity Timesheet

find-a-word addressing work for the dole in indigenous communities, photocopy, A4 paper (2019)

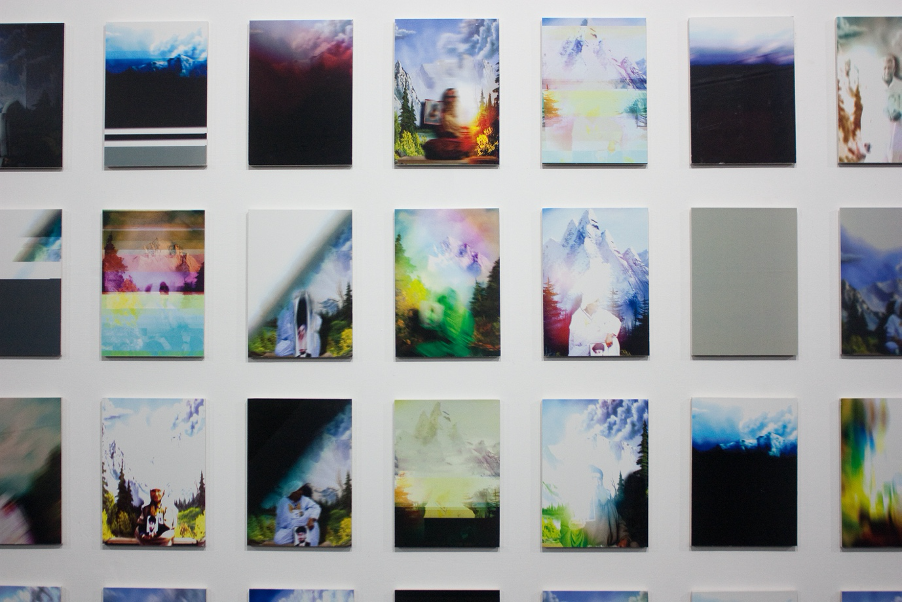

The Incoherent Lives of This and That

lab print photo manipulated found images, HD video, 23 mins (2016)

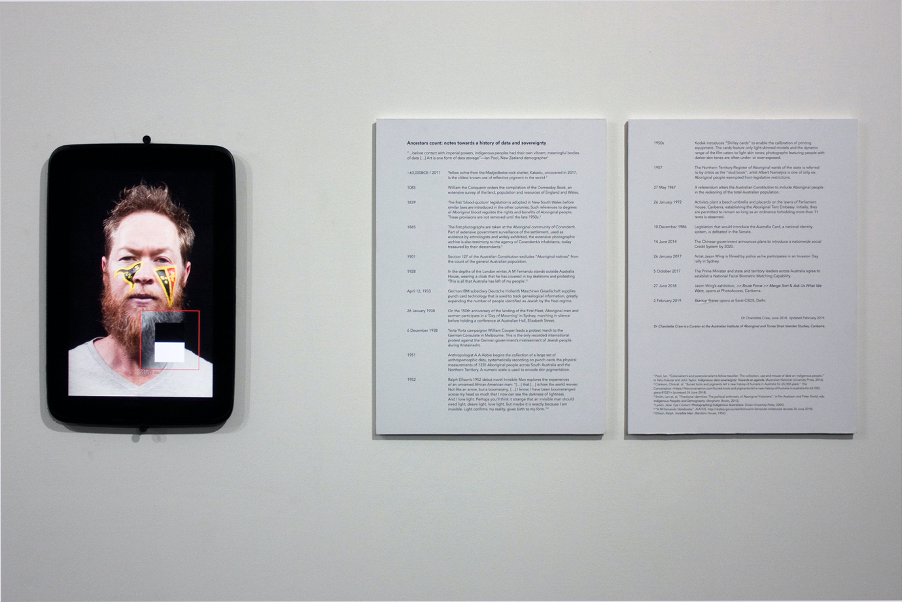

A Rough History (of the destruction of fingerprints)

16mm/HD video, 9:50 mins (2015)